Forty or so million years ago, on the southern end of the Gondwana supercontinent, two mating insects unexpectedly found themselves in a sticky situation - and not in a good way.

Somehow, this pair of busy long-legged flies (Dolichopodidae) had gotten themselves trapped in the gooey sap of a tree, and there was simply no escape. That moment spelled both the beginning and the end of this casual love affair.

Frozen in intimacy, the resin turned to amber, and the moments of copulation turned into something more enduring. In 2011, the precious scene fell into the hands of paleontologists working in the Otway Basin of southern Australia.

At first, lead researcher Jeffrey Stilwell from Monash University said he couldn't believe his eyes. It's not unusual for small ancient creatures to be found in fossilized resin, but for some reason, it's a rarity to find such specimens in the Southern Hemisphere, much less one where two creatures are frozen in the act of mating.

Two matings, long-legged flies trapped in clear, honey-colored amber, approximately 41 million years ago. (Jeffrey Stilwell)

And yes, that's likely what they were doing. Paleontologist Victoria McCoy, who was not involved in the discovery, told The New York Times she thought the picture was pretty clear.

"It's possible one fly was trapped in the amber and the other was a little excited and tried to mate, she said.

Stilwell calls amber the 'Holy Grail' of his discipline because it preserves ancient organisms in timeless animation "looking just like they died yesterday". Previous amber samples have contained parasites in action and creatures in the process of feeding, but the two mating flies are truly astonishing.

"This is one of the greatest discoveries in paleontology for Australia," says Stilwell, adding that this may be the first example of 'frozen behavior' in the fossil record of the continent.

To date, most amber records are from the Northern Hemisphere, so this discovery in southern Australia was enough to prompt a wider search.

Stilwell and his team began looking at sites across Australia and New Zealand, and their recently published results contain a remarkable abundance of amber from the ancient supercontinents of Southern Pangaea, which existed during the Triassic period, and Southern Gondwana, which existed from the Cretaceous to the Paleogene period and included South America, Africa, Madagascar, India, Antarctica, and Australia.

All in all, amongst the haul, the authors report more than 5,800 amber pieces, taken from Macquarie Harbour in western Tasmania - dating to around 54 million years ago - and also from Anglesea, Victoria - dating to around 42 million years ago.

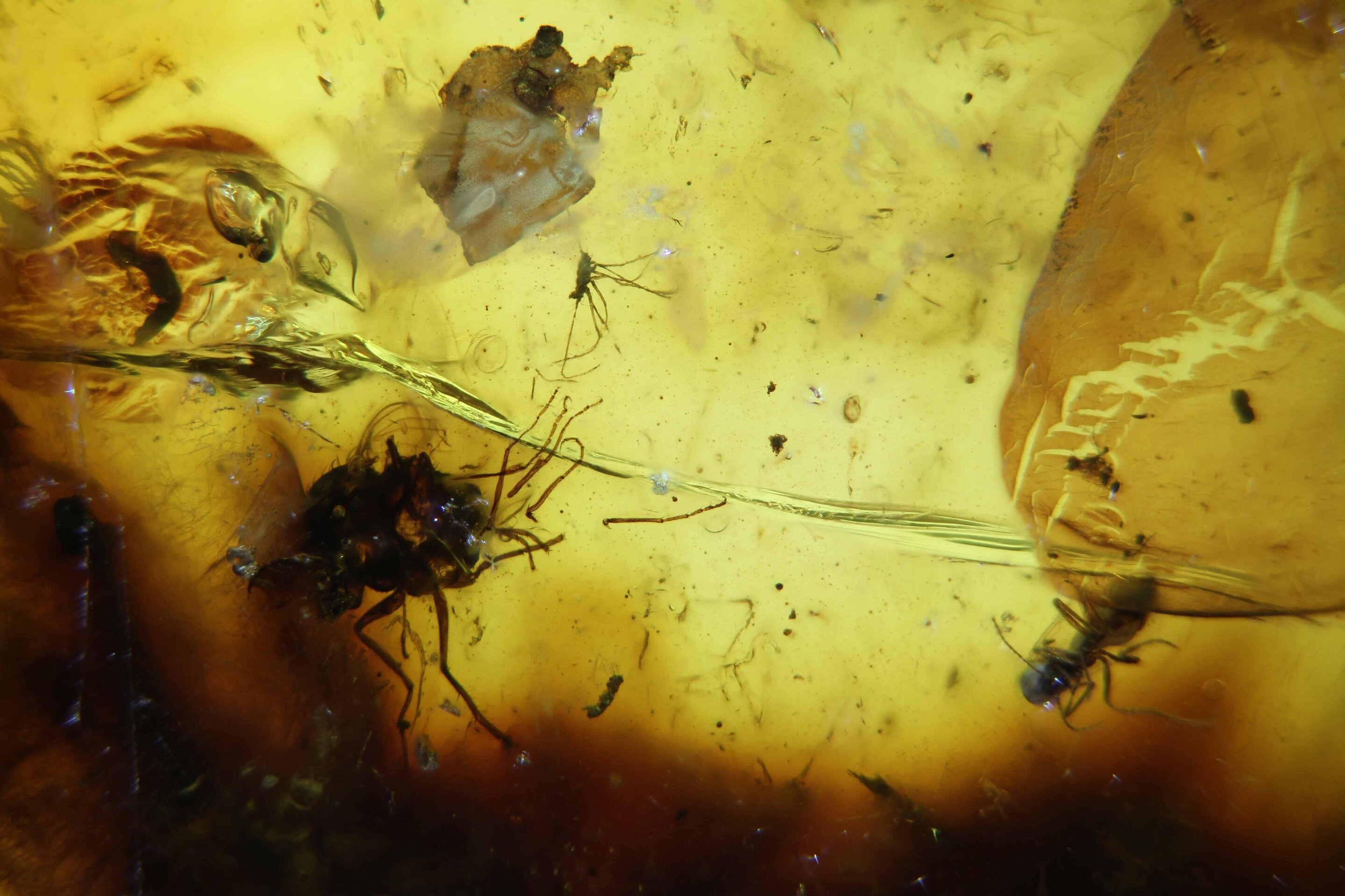

Amber with two flies and the first Australian fossil of a large mite of the extant genus, Leptus dating back 41 million years old. (Enrique Peñalver)

Included are the oldest known animals and plants preserved in amber from Southern Gondwana that we know of. From a cluster of juvenile spiders to biting midges and tiny wingless hexapods, the scenes each one of these amber capsules provides are invaluable, allowing us unprecedented insight into the prehistoric ecosystems that harbored these creatures.

The two mating flies are just the tip of the iceberg, and the authors are buoyed by their find. They think there's more amber out there to be discovered.

Who knows what we could find if we keep looking in unexpected places.

Clear yellow-amber containing a new, beautifully preserved biting midge from approximately 41 million years old. (Enrique Peñalver)

"Despite concerted efforts by many researchers for well over a century," the authors write, "no early Mesozoic or pre-Neogene amber with animal and plant inclusions, has been recovered from Southern Pangaea and Southern Gondwana until this report with scores of new records and vast potential for future finds."

The research has been published in Nature Scientific Reports.

Reviewed by Admin

on

March 20, 2021

Rating:

Reviewed by Admin

on

March 20, 2021

Rating:

No comments: