Sometimes the old methods truly are the best methods. When astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930, it was the result of countless hours spent straining his eyes at a machine called a blink comparator. Using it, Tombaugh could flip rapidly back and forth between two images of the night sky taken at slightly different times.

A NASA citizen science project called Backyard Worlds asks volunteers to do much the same thing, if virtually. Volunteers comb through images of our celestial neighborhood, looking for new worlds near to us, just like Tombaugh. But instead of planets, they’re now looking for something even stranger. The search today is focused on a strange class of objects known as brown dwarfs — not quite planets, not quite stars.

And scientists involved with the project have now released the most up-to-date map yet of brown dwarfs near Earth, something they say wouldn’t have been possible without the hard work of citizen scientists. The map will help astronomers better understand how brown dwarfs form and evolve, and give researchers a better idea of the objects that populate the space just beyond our own solar system.

The Search for Brown Dwarfs

On Tuesday, February 18, 1930, Tombaugh was flipping through recent images when he noticed a tiny dot that jumped back and forth, a sign that he’d found a nearby object. Further observational work ruled out other objects like asteroids, and the discovery of the onetime ninth planet was official. Today, Pluto has been demoted to the status of dwarf planet as we’ve discovered other objects like it in the Solar System.

But astronomers have strong suspicions that we’re not yet done discovering worlds in the outer reaches of the Solar System quite yet. A number of minor planets and other so-called Kuiper Belt objects have been discovered in recent years. And some astronomers think there’s another large planet orbiting far out beyond Neptune, which they call “Planet Nine.”

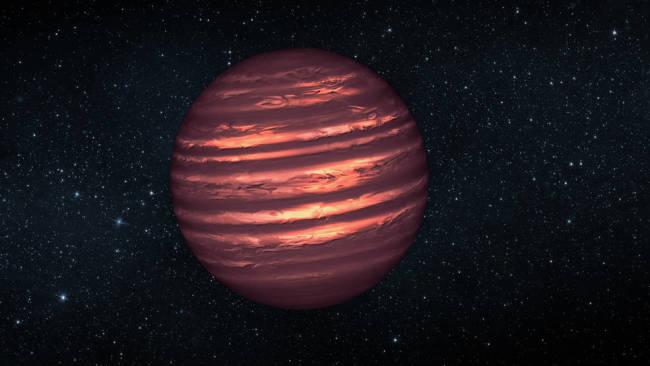

Even further out in our celestial neighborhood there are likely to be a number of dim, mysterious objects known as brown dwarfs. Too large to be planets but not large enough to be stars, brown dwarfs are a strange kind of in-between object. They’re typically defined as being somewhere between 13 and 80 times the mass of Jupiter. The updated map includes 525 brown dwarfs within 65 light-years of Earth, but more are surely waiting out there.

But brown dwarfs are very hard to find, says Davy Kirkpatrick, a scientist with Caltech’s Infrared Processing and Analysis Center and a member of the Backyard Worlds project.

Because they aren’t big enough to begin fusing helium into hydrogen — the process that powers our Sun and other stars — brown dwarfs are often quite cool, meaning they don’t emit a lot of radiation that astronomers can pick up on. Astronomers have found a wide variety of brown dwarfs that differ in terms of composition and internal activity. Still, many questions remain about how brown dwarfs form and what they look like. More observations are needed to get to the bottom of the mystery.

That’s where citizen science comes in. Astronomers already have access to broad, high-resolution photos of nearly the entire night sky, thanks to data gathered from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, spacecraft. Beginning in 2009, the satellite scanned the heavens in various infrared frequencies, and a second phase, dubbed NEOWISE, began in 2013.

Astronomers planned to follow up on anything interesting they spotted in the WISE images with other, more powerful infrared telescopes like the Spitzer Space Telescope. But they soon ran into a big problem: NASA was planning on shutting Spitzer down. To find anything, the scientists would need to move quickly.

“We engaged [citizen scientists] early on to say ‘let’s try to find as many candidates as quickly as possible because we’re running out of time to do this with Spitzer.’ It just barely worked,” Kirkpatrick says. “Without the citizen scientists, we would not have had all those candidates and enough time to do the follow-up. So they were a godsend.”

Volunteers use an online tool to quickly flip through images of the night sky taken a short time apart. If they spot something moving, they’re able to alert astronomers, who’ll follow up on their work with more powerful observations using observatories. Volunteers found dozens of new brown dwarfs candidates that scientists were able to follow up on with Spitzer to help create the new map. In all, the citizen scientists helped add 52 new brown dwarfs in just about a year.

Citizen Science Gives Real Results

Though Spitzer shut down in January of 2020, the astronomers were able to follow up on many promising candidates citizen scientists picked out. This led to the discovery of, among other things, a new class of brown dwarf, called extreme T-type subdwarfs. These objects are extremely old, in some cases around 10 billion years old, scientists think. Other unique observations from the new map include the coldest known brown dwarf, a place where temperatures probably dip below the freezing point.

And other observations are still awaiting an explanation.

“One of the citizen scientists did find a really, really faint object that was just streaking across the sky. And we thought, ‘What is this? This is going to be something weird,’” Kirkpatrick says. The object didn’t match the spectrums of anything they had on file, he says.

Further findings showed it was a very ancient cold brown dwarf composed largely of hydrogen, without the metals most other brown dwarfs have. Kirkpatrick says his team will likely publish a new paper on the object soon, after gathering more data.

Exciting new finds like these may not be the norm, but Kirkpatrick points out that volunteers often find things that researchers miss.

“The citizen scientists, I think partly because they don’t have our preconceived notions, they are more likely to pick out things that are unusual because their eyes aren't attuned to the things we think we’re looking for,” he says.

Kirkpatrick says he’s especially thankful for a core group of a few dozen volunteers who have dedicated numerous hours to the project. One volunteer even coded a tool, known as WiseView, that makes the process of discovering brown dwarfs far easier by allowing participants to flip easily back forth through the images.

Volunteers are invited to listen in on weekly telephone meetings between the scientists as well, where they discuss recent results and new objects to focus on.

“They like to hear the banter back and forth between the scientists because they can hear how science happens in real-time,” Kirkpatrick says.

Reviewed by admin

on

January 31, 2021

Rating:

Reviewed by admin

on

January 31, 2021

Rating:

No comments: